Mimi Schwartz’s latest book, When History Is Personal, makes its debut this March (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). Other books include Good Neighbors, Bad Times: Echoes of My Father’s German Village (2008); Thoughts from a Queen-Sized Bed (2002); and the ever-popular Writing True: The Art and Craft of Creative Nonfiction, co-authored with Sondra Perl (2006). Her short work has appeared in Agni, Creative Nonfiction, ASSAY, The Writer’s Chronicle, Calyx, Prairie Schooner, Tikkun, The New York Times and The Missouri Review, among others—and ten have been Notables in the Best American Essays Series. She is Professor Emerita in writing at Richard Stockton University and gives readings, talks, and workshops nationwide and abroad.

Mimi Schwartz’s latest book, When History Is Personal, makes its debut this March (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). Other books include Good Neighbors, Bad Times: Echoes of My Father’s German Village (2008); Thoughts from a Queen-Sized Bed (2002); and the ever-popular Writing True: The Art and Craft of Creative Nonfiction, co-authored with Sondra Perl (2006). Her short work has appeared in Agni, Creative Nonfiction, ASSAY, The Writer’s Chronicle, Calyx, Prairie Schooner, Tikkun, The New York Times and The Missouri Review, among others—and ten have been Notables in the Best American Essays Series. She is Professor Emerita in writing at Richard Stockton University and gives readings, talks, and workshops nationwide and abroad.

Assay is pleased to interview Mimi Schwartz to celebrate the release of her most recent book. To order When History Is Personal from the University of Nebraska Press, please click here.

Assay (Renée E. D’Aoust):

Mimi, your new book is wonderful—congratulations on its publication! To provide a framework for readers, I’d like to share the description:

When History Is Personal contains the stories of twenty-five moments in Mimi Schwartz’s life, each heightened by its connection to historical, political, and social issues. These essays look both inward and outward so that these individualized tales tell a larger story—of assimilation, the women’s movement, racism, anti-Semitism, end-of-life issues, ethics in writing, digital and corporate challenges, and courtroom justice. In adding her personal story to the larger narrative of history, culture, and politics, Schwartz invites readers to consider her personal take alongside “official” histories and offers readers fresh assessments of our collective past.

In the Preface of When History is Personal, you write that you “count on my experiences clashing with what the world is saying.” Rather than perceiving that clash as a limitation of perspective, you welcome that clash as a necessary, narrative tension. Personal moments connect to historical currents. I’m touching on the idea that the personal is political, but I’m also touching on the idea that individual stories matter. I feel this astute approach to nonfiction is what you’ve developed over the course of your previous books and writing life. Is it something you knew intuitively years ago or something you needed to learn? In writing workshops, we often talk about the courage needed to write our own stories. Is there courage in the clash?

Mimi:

I think being open to clashes—even looking for them—is essential, especially when writing about family and friends we think we know. Childhood memories, in particular, tend to begin with a cast of heroes and villains—the mean father, the jerky sister, the amazing grandmother—who have shaped our miserable or idyllic childhood. Fact checking, interviewing, and research help us challenge our initial assumptions, forcing us to rethink and re-experience remembered stories we are used to telling ourselves. We dig deeper, come in from another angle, hear a counter voice saying It didn’t happen that way! Whatever the clash, memories gains complexity and nuance—and our stories become more insightful.

In When History Is Personal, I benefited from many clashes. There is the one in “The Coronation of Bobby,” when one small fact about King George’s coronation (it happened before I was born) overturned a lovely memory I had of crowning my dog King Bobby, just like King George. And the one in “Love in a Handbag” when a photograph of my sister Ruth and me, high in an oak tree, brings back the good memories I’d forgotten, while writing about our battles half a century later. And the one in “A Trunk of Surprise,” when a speech by an African-American friend makes me realize how much I didn’t know about the racism he had faced before moving into his house in Glen Acres, a wonderfully special community where we met in 1966.

My colleague Jack Connor, in his Argument and Persuasion courses, insists his students include OPV (Opposing Points of View) on every paper. I now urge the same in my writing workshops: by adding dialogue, or telling someone’s counter narrative, or adding one small, annoying fact that overturns a memory. Let the chips of certainty fall wherever. The writing, I’ve found, is truer when the courage for that is there.

Assay:

It is fascinating to me that after escaping Germany and saving his family from the Holocaust, your father took you back to visit Germany, and the small village he had left (and escaped), a mere eight years after World War II ended. Your father has such amazing wisdom, and you write beautifully about your resistance to it and recognition of it. Your writing evokes a profound sense of connection to the world: to place, to village, to family. In the first essay in When History Is Personal, “My Father Always Said,” you write:

Do you want to put down stones?” my father asked, placing small ones on his father’s grave, his lips moving as in prayer, and then on his mother’s grave, and on the others. He had found the stones under the wet leaves, and my mother, wobbling in high heels, was searching for more, enough for both of us.

Throughout this essay and the book, your writing is clear and defined, and it is also very beautiful. Was it hard to find that line of beauty for such profound topics?

Mimi:

If I consciously look for beautiful language, I never find it. The words must come naturally out of the experience I’m describing, or else they tend to sound pretentious and stilted. That said, I try to listen for the rhythms in my head and encourage a rush of words to surface without pre-editing. A good deal gets cut in subsequent drafts, but what remains are the words I most need. James Dickey calls it “finding the nuggets in fifty tons of dirt.” I also like Dorothy Allison’s metaphor of an accordion: “To write-write-write-expand-expand-expand-expand, and then when it is so expanded that it is bloated, cut it down….”

Assay:

As you know I’m a huge fan of dogs in literature. (Right now, I’m working on a survey review of creative nonfiction books about dogs.) Here’s an excerpt from your story of “The Coronation of Bobby”:

Best of all, Omi and Opi had Bobby with his black-and-white tail that wagged like mad whenever we arrived. Unlike the German shepherd next door who bit me, Bobby was a dog for the unafraid, for those who kept trust with the world and chose welcome over anger, optimism over loss and betrayal—and Hitler be damned. My grandparents’ lack of bitterness in choosing Bobby’s good nature was a gift I absorbed without understanding. All that concerned me back then was Bobby’s name. Real Americans, I announced with authority as the first American-born in the family, would call him Spot. Or Sundae, because of his chocolate spots on vanilla fur. Or Silky, for the softest, long ears I ever put my cheek on.

I love that “Bobby was a dog for the unafraid, for those who kept trust with the world and chose welcome over anger, optimism over loss and betrayal.” I know that kind of dog. I recognize the human who befriends this optimistic dog. Also, the photograph of you and Bobby together is adorable. (Further, I also love the mention of your collie Karma in another essay.)

I’m curious if you think there is a different way we need to write about pets from how we write about humans. What do you think is the most frequently missed opportunity as writers when we write about our pets?

Mimi:

I’m so glad you chose the line about Bobby being a dog for the unafraid, because, for me, writing it was revelatory. Before that, I’d been writing a simple romance of how I fell in love with Bobby, and our farm adventures, and how he saved me from the black snake, and how I took him to my house. All true, but nothing I didn’t know; there was no complexity until I realized the other story of my grandparents restarting their previously urban lives on a chicken farm in America—and how memories shaped their lives here. The more I looked underneath and around my simple dog story, the more I found hiding there.

It is easy to idealize the people we love in childhood, and that impulse is probably even greater with pets—especially dogs that offer us so much unconditional love. Writing that one line of surprise led me to reexamine those halcyon farm memories with Bobby when I was five, six, and seven—and made for a more nuanced essay. So my recommendation to others writing about a dog they love? Write at least one line of surprise on your first draft and explore it.

Assay:

I think we’ve both taken part in panel discussions about how to create a book out of a series of essays. Many of the essays included here were published as stand-alone pieces in literary journals (writers should note that your acknowledgement list is an excellent resource of journals to read). I’m completely engaged with When History is Personal, as a cohesive collection. In the preface, you write:

The twenty-five essays in When History Is Personal are meant to talk to each other over time and place. Though the organization is loosely chronological, the echoes and refrains matter more, informing and sometimes undermining a world I think I know. History, I keep finding out, has more than one version even when I am the only narrator!

Was the goal of creating a cohesive book in your mind as you wrote these separate essays? Additionally, how did you come up with a four-part structure for the book? It works so well. Again in the “Preface,” you write, “In four sections, I write to bear witness to the history I’ve inherited.”

Mimi:

In When History Is Personal, the structure came late in the process, after I’d written a dozen of the twenty-five essays in the book. I started by having this image of burying a time capsule of objects when I was eight—and thinking how these essays were like those objects: to preserve the world in my little box of history. I wrote a draft of a preface that began with this image—and then variations of my title came: When History Is Personal. Both preface and title became guidelines for the other stories I told: that each one should combine memoir and history, so that I was always writing about “I” in the world “I” lived in. In other words, I wanted to look inward, as memoir does, and outward at the world that shaped my personal experiences.

My favorite memoirs all did that. Growing Up by Russell Baker, for example, is about “a lazy boy and his mother,” as Baker put it; but also about life as a single mom in the Depression. Baker let me enter that world in a way that I never did reading straight history books. The Road from Coorain by Jill Ker Conway is another favorite because of the way she combines her family story with the world of British settlers trying to make a go of it on the Australian outback.

Finding a structural order for the book only came at the end. My first great idea—to pair a personal essay and a craft essay—flopped. The essays didn’t speak to each other no matter how much I wished otherwise. As my friend, Lynn Powell, pointed out: “In your personal essays, you are discovering. In your craft essays, you have answers. The two voices don’t work well with each other.”

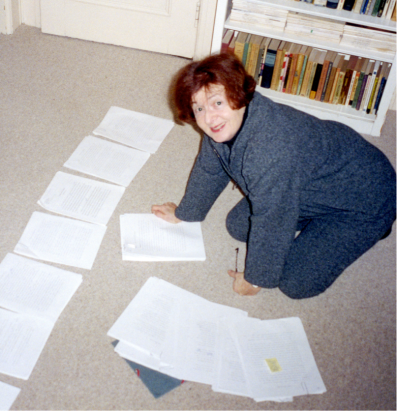

I took away ten craft essays and began looking at poetry collections and other essay collections for new ideas. Somehow were organized by time, but I was drawn to Anne Padgett’s Story of a Marriage, which is loosely chronological but not wed to it. Theme matters more, and with that in mind, I spread the essays out on the floor, and they began talking to each other over time and place. Four groupings appeared—Family Haunts, In and Out My Front Door, Storyscapes, and Border Crossings. I then ordered those groupings, considering tone (the need to mix sad and funny) and length ( the need to vary long and short as in music). Finally, I wanted one essay to lead into the next like links in a chain. I didn’t think it essential that people read sequentially (I often don’t), but if they did, I wanted the dots to connect.

Assay:

In “What’s a Rally to Do?” you implicate yourself in “diplomatic silence,” and you connect the anti-Semitism your parents experienced in Germany with anti-Semitic flyers posted on the New Jersey university where you had taught, at that point, for twenty years or more. You write, “So this is why my dad left Germany! I thought, hurrying off, my heels echoing on the red floor tile. People like her, angry and unpredictable. People like me, diplomatically silent.”

In this essay, you recognize the difficulty of speaking up and speaking with colleagues. The essay shows personal and professional tensions, and it feels almost unbearably current during this political time of division and vulgarity in the United States. Again in the essay, one friend implies that because of your parents’ exodus from Germany you are overly sensitive to the distribution of hate flyers on campus; however, I read it that you are particularly attuned to what those hate flyers mean for the past, present, and future. In this essay, you write, “I always wondered what German professors told themselves in order not to act.” Further, you write:

Platitudes such as “We must treat each other with respect” keep people civil—and connected, like saying, “I love you” on days when you feel the opposite. By themselves these words do little, except to ward off permanent damage; but without them, there is no chance to lay a foundation that might turn self-righteousness into something worth working on.

In what ways can writers further use essays to “turn self-righteousness into something worth working on”? Sometimes I feel personal essays matter because they frame human experience. But other times I admit to feeling rather overwhelmed by the world, to feeling that individual expression, no matter how necessary, is inept. Would you share more about your thoughts about the process of essay writing as it relates to our current political moment?

Mimi Answers:

One lesson, quickly learned when writing about my marriage (one I wanted to stay in) in Thoughts from a Queen-Sized Bed, was to give the opposing voices a chance to make the best argument they can. That translated into: Whenever I called my husband Stu an idiot, he got to call me a moron. It worked. He liked the book, saying You got us right!

One lesson, quickly learned when writing about my marriage (one I wanted to stay in) in Thoughts from a Queen-Sized Bed, was to give the opposing voices a chance to make the best argument they can. That translated into: Whenever I called my husband Stu an idiot, he got to call me a moron. It worked. He liked the book, saying You got us right!

In this new book, I kept that lesson in mind in “At the Johnson Hair Salon,” about liberal versus small town conversation about the opioid epidemic. And about how Israelis and Palestinians see their entwined history in “In the Land of Double Narrative.” And about the issue of death with dignity that my husband and I faced suddenly in “Lesson from a Last Day.” And about my clash with a good friend over what I saw as anti-Semitic incident in “What’s a Rally to Do?” I showed her my drafts; she disagreed vehemently with my version of what happened, and I added that to my story, feeling I gained credibility and a more nuanced truth than I would have otherwise had.

I want people who don’t agree with me to keep on reading. The best way to do that, I’ve found, is to present their side. Which brings me back to Jack Connor’s OPV and how when we add opposing points of view to our personal stories, we have opportunities for understanding and empathy that are lost when we stand alone on a soapbox of self-righteousness.

I just read an interview with the Lebanese filmmaker, Zaid Doueiri, whose films gain their power from presenting both sides, be it between Israelis and Palestinians (The Attack) or Christian Lebanese and Palestinians (The Insult, his latest). When asked why, he said, “As an artist, it is your moral duty to understand the other side.” That includes all of us who write our lives.

Assay:

You are a long-time professor of creative nonfiction, and you’ve also been a guest teacher at many writing workshops nationally and internationally (including in my adopted country Switzerland at the Geneva Writers Workshop). My colleague (at North Idaho College where I teach online) Jon Frey and I were talking about your craft text with co-author Sondra Perl, Writing True: The Art and Craft of Creative Nonfiction.

Jon Frey mentioned how much he loves your chapter on voice and writes: “Voice is something that I struggle with in my own nonfiction, and it feels so ephemeral that I almost hesitate to bring it up with undergrad writers for fear of sending them into spiraling self-doubt and crippling angst. So, I would love to ask Mimi Schwartz two things:”

1. How do you talk to students about techniques that feel mysterious to you without making writing feel precious and inaccessible?

2. What role do exercises and forced experimentation play in helping students find their own voices?

Mimi:

When I think of voice, I think of authenticity—and which of our many selves is the best “I” to tell a particular story. Revision, for me, is often about finding the right voice of that narrator. In my opening essay “My Father Always Said,” for example, I started in the voice of my thirteen-year-old self and was going strong until page six. Then I got stuck, until many drafts later I realized this bratty teenager could not narrate her father’s response, near his ancestral graves, to the echoes of the Holocaust. Only when the adult me arrived, or as Sue Silverman it, “the voice of experience” replacing “the voice of innocence,” was I able to reflect on the experience and finish the essay. I say, “when the adult me arrived” because it came out of experimentation. I told myself Let me try switching tenses (I went from present to past) and “try” was key. I read the new voice on the page and knew this was the right one for this story. But I had to coax it, not command it.

With my students, I rely on prompts, written and shared in class, to coax out their authentic voices. They just appear, and everyone in the room hears them and welcomes them—so they stick around for whatever story they might tell next.

Assay:

Thank you for your time and, again, congratulations on your beautiful book—and body of work! We so appreciate you visiting Assay’s “In the Classroom” series.

To order When History Is Personal from the University of Nebraska Press, please click here.

****

Renée E. D’Aoust’s Body of a Dancer (Etruscan Press) was a Foreword Reviews “Book of the Year” finalist. Seven essays have been named “Notable” by Best American Essays and “Gratitude is my Terrain,” published by Sweet: A Literary Confection, was named one of “2016’s 30 Most Transformative Essays” by Sundress Publications. She was an NEH Summer Scholar at the “City, Nature: Urban Environmental Humanities” 2017 Summer Institute, and she has twice served as a Writer to Writer mentor for AWP. D’Aoust teaches online at North Idaho College and Casper College. Please visit www.reneedaoust.com and follow her @idahobuzzy.

Renée E. D’Aoust’s Body of a Dancer (Etruscan Press) was a Foreword Reviews “Book of the Year” finalist. Seven essays have been named “Notable” by Best American Essays and “Gratitude is my Terrain,” published by Sweet: A Literary Confection, was named one of “2016’s 30 Most Transformative Essays” by Sundress Publications. She was an NEH Summer Scholar at the “City, Nature: Urban Environmental Humanities” 2017 Summer Institute, and she has twice served as a Writer to Writer mentor for AWP. D’Aoust teaches online at North Idaho College and Casper College. Please visit www.reneedaoust.com and follow her @idahobuzzy.